Haters Gonna Hate

October 31, 2012 1 Comment

A web-comment in my local newspaper today claims ” the main body of scientists did not have high enough ethical standards to remain credible.” His comment was directed at the author of an article discussing climate change, one of the many news articles that are obviously politicizing the damage done by hurricane Sandy. Heaven forbid, of course, that we acknowledge a natural disaster should force us to ask questions about governmental responsibility (FEMA, the National Weather Service, and first responders), personal responsibility (evacuation), economics (pre-storm sales, insurance, lost business, state costs versus federal relief), and which politician might be most well suited to handle such issues. (Hint: Mitt Romney wants to cut FEMA and give out block grants to states. I think. Or, at least, he did during the primaries.) There is, the comment in the paper goes on, no real evidence humans are impacting the climate.

A web-comment in my local newspaper today claims ” the main body of scientists did not have high enough ethical standards to remain credible.” His comment was directed at the author of an article discussing climate change, one of the many news articles that are obviously politicizing the damage done by hurricane Sandy. Heaven forbid, of course, that we acknowledge a natural disaster should force us to ask questions about governmental responsibility (FEMA, the National Weather Service, and first responders), personal responsibility (evacuation), economics (pre-storm sales, insurance, lost business, state costs versus federal relief), and which politician might be most well suited to handle such issues. (Hint: Mitt Romney wants to cut FEMA and give out block grants to states. I think. Or, at least, he did during the primaries.) There is, the comment in the paper goes on, no real evidence humans are impacting the climate.

What is most troubling about the comment is not the idea that some random citizen in my home town ignores the logical reality that exponential growth in the number of humans is not impacting the climate. To a certain extent, this is like arguing that increasing the number of students in a class room won’t impact the learning environment. Or, adding more vehicles traveling on a certain road won’t increase the wear and tear. Or, adding more sugar to our diets won’t increase our weight. Or, in case those are examples that don’t make sense: it’s like arguing that adding fans to a football stadium won’t increase the noise level. More people equals more impact. Duh.

But that’s not what bothers me about the comment. The elemental distrust of our citizen scientist is almost stunning in it’s dismissal of the scientific community. His (or her) comment isn’t just a sign of ego run amok; this is an argument claiming a vast scientific conspiracy by scientists across the world to falsify data. These are, I can almost hear our not-a-darwin, the very same scientists who believe in evolution! These “scientists,” he might write, are driven not by numbers and methods of inquiry that require replication but by secular, god-less politics.

Cognitive scientists tell us “Weighing the plausibility and the source of a message is cognitively more difficult than simply accepting that the message is true — it requires additional motivational and cognitive resources.” In other words, truth, learning, and understanding is hard work. It’s doubly difficult if the information is counter to our accepted beliefs and, when we are feeling intellectually lazy, we all turn into the Dude: “That’s just, like, your opinion man.” Or, as my students might say: it’s all good.

Except it’s not all good. Our commentator represents what appears to be a growing narcissistic willingness to dismiss science or facts when the inconveniently disagree with what we can easily believe. Note that I’m not talking about honest debate regarding numbers or ideas. I think we can have a healthy and intelligent debate about what we should do about climate change. What is the government responsibility with regards to curbing population growth and the use of those things we know damage the environment? Maybe nothing. Perhaps, one might argue, the government is not the moral authority or our parent and if populations or nations want to drill for cheap oil that is our choice. Or, perhaps we want to argue that governments are designed to reign in public consumption when that consumption creates larger problems that individuals can’t handle by themselves.

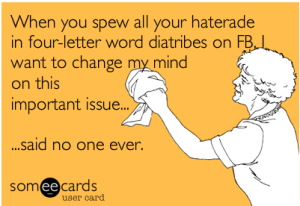

But we can’t have intelligent, intellectual discussions when people simply dismiss reality because it creates cognitive dissonance. The position that evolution, climate change, gravity, or any other scientific truth is the product of a conspiracy is unconscionable and counter-productive. We have a responsibility to reject, ignore, and correct those people who blatantly reject reality as if they are the only ones privy to truth. One wonders if we pushed if our letter writer would, in fact, say what he means: the main body of science is not as smart as me.

If this idea was the isolated rant of a lone man living in a cabin, I don’t think I would care as much. We could dismiss him as the cranky guy down the street who also yells at the kids to “get off the lawn.” Unfortunately, our letter writer sounds like too many of our politicians running (and being elected). When states begin requiring that schools teach “alternative” theories of creation, when politicians insist that women’s bodies can prevent pregnancy during rape, when major political parties support candidates who call the big bang theory, evolution, and embryology as “lies straight from the pits of hell,” we might consider taking this seriously.

Or, we can take the path of least resistance. A few more storms like Sandy and we won’t have to worry about it.